School buildings which support pupils and planet

Alongside the need for our built environment to operate within the boundaries of our natural environment, the schools we build must perform well to meet the needs of teachers and pupils. So what does a successful sustainable school building look like? The UK Green Build Council’s Alex Benstead shares some thoughts

Record-breaking temperatures this summer sent a clear signal that climate change, along with its hazards, is well-and-truly here. Every effort available to us to limit temperature rises below 1.5C must be made, including when it comes to the buildings within which we live, work, and teach. Many of the solutions to delivering sustainable buildings, which both protect and enhance nature, already exist in today’s market. Delivering them at the scale necessary to ensure we meet our climate targets is the current challenge we face and one we must overcome.

With the built environment directly responsible for around 25 per cent of the UK’s carbon footprint, it is mission critical to our climate targets that we transform the way all buildings - including schools - are planned, designed, constructed, maintained, and operated. That is precisely why it is UK Green Building Council (UKGBC)’s mission to radically improve the sustainability of the built environment. With over 700 organisations spanning the entire sector, our members are at the forefront of driving sustainability.

What does a successful school building look like?

Alongside the need for our built environment to operate within the boundaries of our natural environment, the schools we build must perform well to meet the needs of teachers and pupils. What does a successful school building look like, and how can we continue to create that within our planetary boundaries?

RIBA’s Caroline Buckingham offers a compelling response to this question by suggesting “a good school is driven by its educational vision and ethos. The role of school buildings, whether new or partly refurbished, can facilitate this vision. In school design there are many common parts, teaching spaces, staff spaces, and large spaces.”

However, Caroline stresses that while one size does not fit all, a good school building needs to be “eliminating challenges such as cramped spaces, lack of natural light, and bad acoustics.” And when it comes to those who occupy them, a good school building should be “welcoming and uplifting, providing a sense of ownership and pride for pupils and staff.”

For me, this is the exciting part of design, uncovering building solutions that not only perform well functionally and aesthetically, but also exist within the capacity of our planet. If we are educating children to thrive within society, then we should be helping to protect that very future through our actions.

School buildings for net zero and future generations

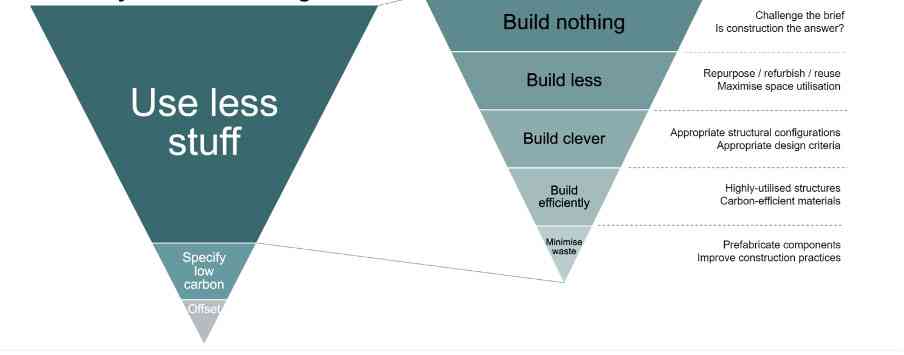

When considering the need for any development, one of the best places to start is the Institution for Structural Engineers’ Hierarchy of Net Zero Design. Not only does it challenge us to understand whether a new build is truly necessary, but it asks us to consider whether we can continue with existing structures and rethink the space we already have. In a country with an estimated 165,000 empty premises, it makes sense to re-use our existing stock.

Figure 1: The Hierarchy of Net Zero Design, Institution for Structural Engineers

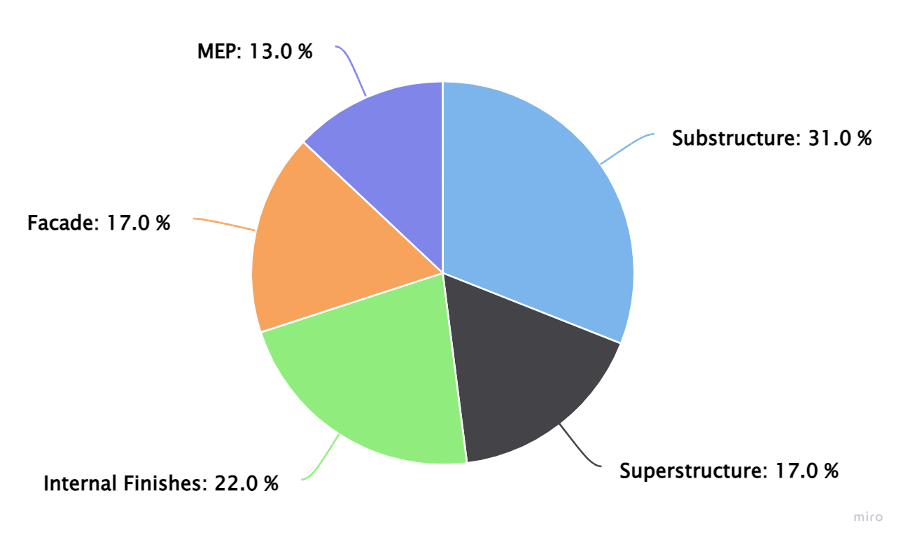

The Hierarchy of Net Zero Design steers industry to firstly consider not building at all, followed by seeking out opportunities to refurbish and renovate, ultimately resulting in building less. During a renovation project the typical aim is, at a minimum, to keep the core structure. Nearly half of the carbon emissions associated with constructing new school buildings come from the foundations and main structural frame – by choosing to retain as much of the existing structure as possible, considerable carbon savings can be made. This can be taken even further through preservation of the facade. While working with existing buildings can be challenging, prioritising renovation over new build is where we will have the largest impact. It is a challenge we should be tackling head on.

Figure 2: Embodied Carbon Emissions breakdown per element within a typical School, LETI Climate Emergency Design Guide, leti.uk/cedg

Solutions to build more sustainably already exist

Now we’ve looked at whether we need a new building, the next step towards net zero design is to build clever. How can we design in a way that uses fewer materials, uses low carbon materials, and focuses on longevity and adaptability. These principles start to take us into a circular economy approach. Moving from a linear take-make-waste industry, to one that recognises the value of materials and prioritises keeping hold of their functionality.

Focusing on materials, a well-designed building will firstly explore all opportunities to reduce the amount of material used, this may produce design options that weren’t previously considered as reducing emissions becomes the top priority. Secondly, and hand-in-hand with reducing material volume, we should be using low carbon materials, such as sustainably sourced timber. Concrete and steel are typically the highest source of carbon emissions, and if it isn’t possible to design them out, then it’s possible to use a high proportion of cement replacement, reused steel, or steel with a high recycled content.

In terms of the building concept, we should be designing for sustainability across the lifetime. In the construction phase, this means designing with standardised, prefabricated, and modular products. Waste is a significant problem for the construction industry and exploring solutions such as off-site manufacturing can have a positive impact on reducing waste. We also need to consider how the building may need adapting in the future, as needs can change over time. An adaptable building that can be easily disassembled or remodelled prevents future emissions and resource use. It’s easy to see the value of this as we look at our current buildings and the complexities involved with renovation.

As we design for net zero, it’s important that there’s a common understanding of what we’re aiming for, how we measure it, and how we confirm that a building has indeed reached Net Zero. UKGBC have done foundational work on this, with our Net Zero Carbon Buildings Framework released in 2019, to provide the industry with clarity on the definition of Net Zero buildings. Improving on this further, UKGBC are collaborating with other leading organisations to develop the Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard; an agreed methodology. If you’re in the process of designing a new school, or planning a future one, then it would be wise to consider both the UKGBC Framework and the upcoming Standard.

Going beyond carbon, we should also explore how a school sits within its environmental surroundings, considering its wider ecological impact and the benefits of incorporating nature-based solutions. Options such as green walls, sustainable drainage systems, and green space play a critical role in futureproofing buildings, providing much needed adaptation to climate-related risks such as flooding, whilst also delivering benefits for biodiversity and nature. When it comes to schools, the positive outcomes of enhancing on-site nature are massive, with natural environments shown to increase academic performance, motor skills, and rates of physical activity.

The time to act responsibly is now

Designing for net zero – and future generations – is both an opportunity and a challenge, but one that should be pursued by all. Not least because the solutions exist, but because it provides a better outcome holistically, with school buildings that are aesthetically pleasing, comfortable, functionally adaptable, and inspiring for the pupils. But further than this, designing sustainably is about understanding the complex world we inhabit, acting responsibly both for ourselves and others, and not shying away from the challenges in front of us.

Further Information:Latest News

19/12/2025 - 09:54

The Education Committee has expanded its ongoing inquiry into the early years sector to examine how safeguarding can be strengthened in early years settings.

18/12/2025 - 09:25

The UK will be rejoining the Erasmus programme in 2027, following a package of agreements with the EU.

17/12/2025 - 09:31

Ofqual has fined exam board Pearson more than £2 million in total for serious breaches in three separate cases between 2019 and 2023 which collectively affected tens of thousands of students.

16/12/2025 - 09:19

The average funding rates will increase by 4.3% for under 2s, and by almost 5% for 3-and-4-year-olds.

15/12/2025 - 10:30

Local colleges are set to receive £570 million in government funding to expand training facilities in areas such as construction and engineering.