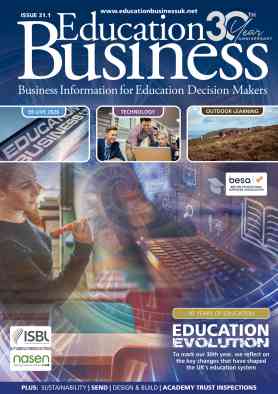

A new approach to outdoor learning

It’s not easy being a young person in Britain in the 21st century. On a range of indicators, young people are starting from a poor position. In health, many must contend with a range of tenacious issues. We have concerns about sedentary lifestyles and children ‘wrapped in cotton-wool.’ Obesity is increasing. Some young people for the first time in generations are more likely to die earlier than their parents. Confidence is a major concern and research shows many young people have a pessimistic view of their future. How might we build confidence when austerity is likely to undermine it?

Disconnected with the planet

In environmental terms, many young people remain disconnected from the wider environment. Research shows some young people believe that eggs come from cattle and milk from cartons. When one Youth Parliament narrowed down their priorities of concern, they marginalised issues relating to sustainable development. Clearly, sustainable development is an international approach that will be of great importance to them. But possibly, like most young people being brought up in cities and towns, they currently do not see the environment as relevant to them. How will they ‘save the planet’ if they consider it an irrelevance?

Globalisation will demand new skills and abilities. Historically, we have contributed in business and politics throughout the world. But in the future, teams in the workplace will be more multinational. It has been suggested that 40 per cent of jobs today did not exist 20 years ago therefore it is unclear what the jobs will be that our children will do. How do we prepare them for jobs which do not yet exist?

Young people should not model themselves on the current generation. Today’s decision-makers tend to reflect the population at large in their dislike of change. We are reluctant to adapt to changes in our lifestyles and resistant to changes in working practices.

Yet young people need to see the world differently from us. They must see the opportunities in change and not just the threats.

Herein lies a great challenge. We must enable young people to develop differently from us, and be more skilled than us. We must help young people to develop the qualities, skills, knowledge and experiences to enable them to survive and thrive in the world of rapid change. And this must happen despite of a pervasive narrative of austerity.

Residential Outdoor Learning

Residential outdoor learning can be life affirming, even life changing but primarily it is a powerful approach to the development of the qualities, skills, knowledge and competencies that young people need. High quality residential programmes develop:

• confidence, optimism and a ‘can do’ spirit

• the ability to make decisions in the face of complex and daunting challenges

• motivation and hence be more successful learners

• positive attitude toward problem solving;

• resilience, tenacity and determination

• adaptability

• understanding of risk, risk assessment and risk management

• creativity both initiating and being receptive to innovation

• knowledge and appreciation of healthier and more active lifestyles

• ability to reflect on their own potential and contribution to society

• appreciation of others, their place contribution and potential in the world

• team work and strong communication skills

• leadership qualities

Such programmes are motivating, challenging; even fun. They must be if young people are to be receptive to learning. But we should not underestimate the potential of the residential experience for learning and personal and social development. During a five-day residential, young people develop at a step change from where they were before.

Developing in young people these qualities, skills and competencies will ensure they are prepared for whatever the future will throw at them. The remarkable contribution of the residential experience is that it can deliver so many outcomes simultaneously. How does it do this?

The New Approach

First, it is important to distinguish the new approach from that of the past. The new approach redefines outdoor learning. More than just helmets, harnesses and muddy boots, and more than just distraction, fun and sport, intelligent outdoor learning integrates motivating and challenging activities with clear learning and PSD outcomes, and the immersion of a young person in a friendly and safe, away-from-home environment.

While the constituent parts have been around some time, teachers and other education professionals need to be aware of the powerful efficacy of these factors working in combination. Their integration creates the added value of innovation necessary to meet the very specific needs of schools and pupils.

There are many specific outcomes but residential outdoor learning is particularly effective in developing confidence in young people. Through a programme of carefully managed challenges and achievements, young people emerge with an enhanced understanding of their potential. They should all leave, clear in the knowledge, that their potential is far greater than they previously thought.

It is important to keep in mind the wider picture. The goal should be for all young people to benefit from regular and frequent outdoor learning experiences throughout their school life in: schools grounds, in local green spaces, within their local community at scouts and guides, and in expeditions in Britain and overseas. All can be powerful experiences in their own right. But a young person on a trajectory of multiple experiences will perform better in school and be better prepared for their future.

An experience

Notwithstanding this range of possibilities, the residential experience is a vital component. Usually occurring between upper primary and secondary, it is the strengthening interconnector between the good work done in primaries, in school grounds and local communities, and the specialisation and award opportunities in secondary schools. The immersive quality is almost a rite of passage.

For success in terms of multiple benefits, it is essential to recognise continuity and progression in different experiences. This highlights the importance of collaborative working between school and centre educators both before and after the residential experience.

Progression is made possible through genuine partnership working between professional educators. The ability of specialist centre educators to use a range of motivating activities while emphasising multiple outcomes, for the full range of ages and abilities, is made possible through familiarity of use with activities at the centre. Skills are used that require constant practice for confident delivery and are not easily picked up for just a few hours during the year.

Residential centres are one of the few organisations to work with all young people and organisations from independent, special need and local authority sectors. The combination of resources, innovative needs-based programmes and specialist staff teams provide the essential pre-requisites for partnership working.

The residential is an important element in the progression of outdoor learning experiences. It also contributes to continuity. Some 14 and 15 year old pupils may be offered one of several award schemes at which point many say no. But had they been involved in a residential experience a year or two preceding, there is an increased likelihood that they will recall having enjoyed the experience and know that there are things they can do and value doing in the outdoors.

Creating relationships

A five-day residential experience equates to around two full weeks in school. It creates a time when teachers and pupils can spend time together and see each other in a different light. With a specialist outdoor educator and a teacher working together, the ratio may be nearer 6:1 (young people to adults). Opportunities for in-depth conversations, shared understanding and meaningful relationships are greatly enhanced. One secondary teacher with responsibility for transition captured this, saying of a residential that: “It has been great. In five days I have developed a rapport with these children that would have taken three months in school.”

There is also evidence that residential experiences trigger behaviour changes away from those which impede learning and personal development. For example, one primary class included a pupil who had restricted his diet while another pupil had determined to be mute in school. Within a few hours of a residential stay, one was tucking in to a wide range of healthy food types and the other was talking to teachers and outdoor tutors and singing in the shower. People working at residential centres know that such examples are regular occurrences.

However, the notable points are that one pupil had been attending meetings with a dietician for six years with no noticeable improvement. The other pupil had been attending meetings with child psychologists also for six years, also with no noticeable improvement. Yet being in the outdoors, doing motivating activities, in a friendly, safe environment, enabled these young people to trigger their own fresh starts.

It is important to anticipate that the residential experience delivers not just one or two, but many benefits and outcomes. While the pupils above were making important changes to the benefit of their personal and social development, they and their class mates were also learning about rivers and the hydrological cycle, co-operative working, and many other things that supported the work of the class teacher.

It is the ability to produce specific, tangible and multiple outcomes, that makes the residential experience so highly cost effective.

Conclusion

Intelligent outdoor learning is a new approach to residential experiences and teachers will wish to be aware of this powerful pedagogical approach.

It addresses many long standing and contemporary challenges and enables young people to develop the qualities, skills, knowledge and experiences they will need to live and work in the world they will inherit.

This may seem a daunting task but anyone who sees young people regularly at residential centres knows that they will rise to the challenge. It is our responsibility as adults, educators and decision makers, to see they get the chance.

Latest News

10/02/2026 - 09:47

Spending on schools across Scotland has increased by more than £1 billion in real terms over the past decade, statistics show.

10/02/2026 - 09:34

New training to empower school staff to improve mental health and wellbeing support for neurodivergent students has been launched by Anna Freud, a mental health charity transforming care for children and young people.

09/02/2026 - 09:58

Data from BAE Systems’ annual Apprenticeship Barometer found that 63% of parents said they would prefer their child to choose an apprenticeship over a degree after school.

06/02/2026 - 09:59

The work builds on guidance launched by Cardiff Council in autumn 2025, which provides clear and practical advice for schools responding to incidents where weapons are brought onto school premises.

05/02/2026 - 10:40

Schools are invited to take part in a practical, hands-on roundtable at Education Business LIVE 2026, exploring the complex relationship between wellbeing, attendance and behaviour in schools.