Creating the people the future needs

Young people deserve to experience a broad and balanced curriculum which recognises the importance of design, argues Catherine Ritman-Smith of the Design Museum.

One of the many issues facing schools today is the subject choice they offer their students. The decisions will be driven by how to enable students to achieve their best and to equip them for employability, as well as financial considerations, with some subject provision draining strained budgets. Not least, schools are concerned about accountability and how they will be evaluated.

On 4 July this year, the proposed new English Baccalaureate (EBacc) will be debated, having gained over 100,000 signatures on a Parliamentary petition which called for expressive arts to be included in the curriculum. The new EBacc will require pupils to be entered into a minimum of seven subjects from a prescribed list – English literature and English language, maths, double or triple science, a modern and/or ancient language, history and/or geography. If students take triple science, history and geography, this goes up to nine GCSEs. The average number of full GCSEs taken by students is 8.1. This leaves little room for creative subjects.

The creative industries represent 5.2 per cent of the UK’s economy, contributing over £84 billion in 2014, growing by almost 10 per cent between 2013 and 2014, and employing almost two million people. This is a sector which offers important employment potential for young people in our schools today. But it’s not just those who want to work in the sector which benefit from the inclusion of creative subjects. These subjects have proven value for all students.

For some schools the provision of Design and Technology is seen as challenging. Yet, if it were evaluated more thoroughly the benefits would be easily convincing. Design is a subject equipped to be at the heart of twenty-first century education, creating the people the future needs. Design is solutions focused, recognising problems and seeking opportunities to effect change. It calls upon creative, imaginative, analytic and propositional thinking, demanding higher order processing to move from the ‘what if we?‘, ‘how might we?‘ questions that spark a design process to resolve these into real outcomes. This enables young people to engage critically with the made world and to make informed choices as consumers and producers. It also develops skills which positively impact across the other subjects they study and beneficial for what they do later in life.

But design education in schools is at a critical juncture. This isn’t the prescient defining moment of 1988 when Design and Technology became a subject in its own right in the new national curriculum. It set up a fresh paradigm as a problem-solving subject, becoming a core component within the educational foundation upon which today’s successful creative industries are built.

Instead, the subject is at the brink of potential decline with what would result in disastrous long-term effects for the flow of suitably skilled young people into higher and vocational education and into industry.

The exclusion of creative subjects from the EBacc remit; subject silos; out-dated subject orthodoxies; teacher shortages and financial and academic pressures on schools weighed down by accountability measures are creating a perfect storm in which students will be those affected in the short term and society in the long term.

Late last year, DATA, the Design and Technology subject association, launched its manifesto, Designed and Made in Britain…? D&T in schools is critical to the UK’s future success. At its launch a panel of expert practitioners from education and industry made compelling arguments for a pragmatic, solutions-focused call to action across government, awarding organisations, Ofqual and the broader D&T community.

Why design education in schools needs to be sustained is powerfully articulated in the excellent Design and Technology curriculum Purpose of Study, which bears quoting in full: ‘Design and technology is an inspiring, rigorous and practical subject. Using creativity and imagination, pupils design and make products that solve real and relevant problems within a variety of contexts, considering their own and others’ needs, wants and values.

They acquire a broad range of subject knowledge and draw on disciplines such as mathematics, science, engineering, computing and art. Pupils learn how to take risks, becoming resourceful, innovative, enterprising and capable citizens. Through the evaluation of past and present design and technology, they develop a critical understanding of its impact on daily life and the wider world.

High-quality design and technology education makes an essential contribution to the creativity, culture, wealth and well-being of the nation’.

This last point about wealth is particularly pressing given the needs of industry and employability. NESTA research describes a future in which the UK will need one million more people to fill new creative jobs by 2030 – the type of jobs that won’t be automated because they require creative and discretionary judgement. Meanwhile, Engineering UK tells us that by 2022 we will need 1.82 million new engineers, whilst the CBI’s campaign Raising Ambition for All is based on significant shortfalls in young people’s ‘work readiness’, an issue addressed by Inspire the Future, the UK Commission for Employment and Skills’ programme.

Design education teaches not only the skills and knowledge that the future economy demands, but also the concomitant attitudes and behaviours. These include resourcefulness, creativity and imagination, innovative and enterprising thinking, the ability to work in a team, to see a project through to completion, with a solutions-focused approach.

At the DATA manifesto launch, arguments were strong for the wider benefits of the subject. David Anderson, head teacher at Queen Elizabeth’s Grammar School in Faversham, himself a former head of Design and Technology, cited prior professional experience of attainment improvements across the board when students also studied D&T. But academic achievement is not the only necessity of a skilled workforce for the twenty-first century education: whilst China may be producing high PISA achievers it also recognises a shortage of ‘creative problem-solvers’.

We welcome up to 25,000 learners annually to the Design Museum. We see the strongest models for design education as those that connect students with real world contexts and the professional practice of design. These models are shaped by schools in which the head and senior management team are enthusiastic about design and understand the subject as integral to their curriculum, with intrinsic as well as cross-curricular benefits.

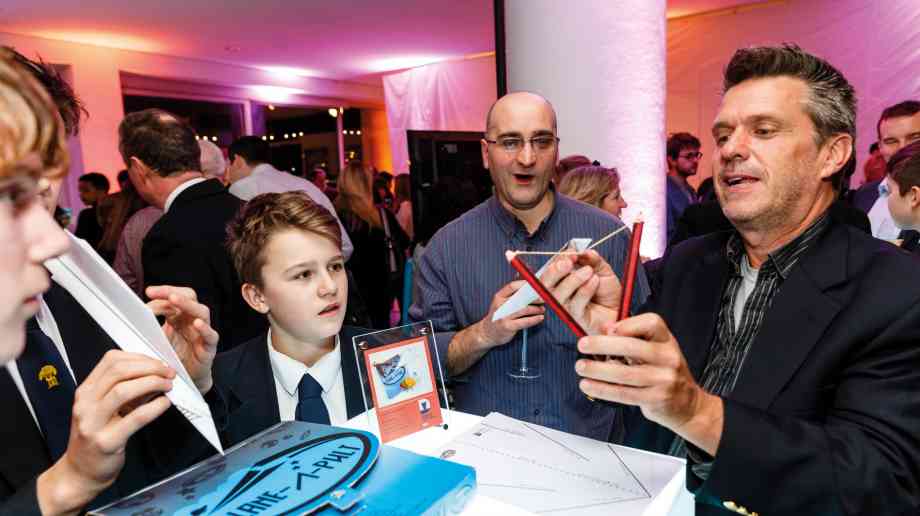

Relevancy as well as leadership is critical, and can be achieved through themed, project based teaching, drawing on local contexts, with links to industry and inspirational examples of design. Design Ventura, the museum’s annual Design and Enterprise programme funded by Deutsche Bank, provides a one stop shop for a real world, relevant design experience and supports teachers’ aspirations for their subject and students, providing a route to design skills that they may not otherwise encounter in traditional classroom or workshop set ups.

Students work in teams and adopt roles that model professional design practice (creative, communications, finance) to respond to a real life brief set by leading designers such as Barber & Osgerby of Olympic Torch fame. The project has a positive effect on the status of the subject both in school and in the eyes of the young people. Teachers gain in confidence and understanding of the value of cross curricular approaches to design.

An independent review last year found that all participating teachers reported that Design Ventura had a very positive impact on students’ design and business capabilities. Ninety per cent of students acknowledged greater confidence levels in solving design problems.

Of wider impact was more general growth in confidence and in aspiration – a vital motivator for all students to achieve. Nine out of 10 students agreed they were more focused about the skills they needed for the future and what they are able to achieve through studying. Over 90 per cent of students had a better understanding of working in a team, presenting ideas to others and accepting that ‘mistakes and criticism can be useful as they help you learn and improve’.

These are the very skills for which industry leaders are calling. In 2015, members of The Institute of Directors cited the shortage of ‘soft skills‘ in employees as the number one barrier to growth. Two thirds (68 per cent) were worried about poor communication skills, 35 percent teamworking, 36 per cent resourcefulness and 22 per cent creativity.

Both the Cultural Learning Alliance and the Creative Industries Federation are actively looking behind headline statistics, made to appear rosy, and calling for greater commitment to a curriculum which supports both individual growth and in turn the economy. The current danger with a drive to competitive educational attainment, a curriculum will be adopted that will squeeze out creative subjects – at great cost.

Author and policy educationalist, Yong Zhao, warns: “If Western countries successfully adopt China’s model; and abandon their own tradition of education, they may see their standing rise on the international tests, but they will lose what has made them modern: creativity, entrepreneurship and a genuine diversity of talents.”

A report published by McKinsey and Company in 2005, China’s Looming Talent Shortage, found that the Chinese system produces students who excel in a narrow range of subjects with only 10 percent of its college graduates considered employable by multinational businesses because the students lack the qualities society needs.

Connecting young people with real world examples, creative practitioners and industry is the means of shaping a curriculum which best serves us all. Schools will benefit from industry rolling up its sleeves and working more closely with them. From my perspective as a cultural sector professional, there is an important opportunity here for us to create programmes that broker those connections.

Young people need and deserve to experience a broad and balanced curriculum offer in which creativity and imagination, coupled with real world application and industry insight, are writ large. Only then will education create the people the future needs.

Further Information

www.designmuseum.org

Latest News

08/01/2026 - 10:30

The government is launching a new app allowing students to view their GCSE results on their phones for the first time from this summer.

08/01/2026 - 09:45

Education Business LIVE has announced that Professor Samantha Twiselton OBE of Sheffield Hallam University will speak at the event in March 2026, delivering two thought-provoking sessions focused on initial teacher training and SEND provision.

07/01/2026 - 10:10

Solve for Tomorrow is a free, curriculum-linked programme which is mapped to Gatsby Benchmarks 4, 5, and 6, helping teachers embed careers education without adding to workload.

06/01/2026 - 10:24

London's universal free school meals programme has not led to improvements in pupil attainment during its first year, but has eased financial pressure and reduced stress for families.

05/01/2026 - 10:44

New regulations have come into force from today, banning adverts for unhealthy food and drinks before 9pm, and online at all times.